Special thanks to Maṣ̌a from Zelena omladina Srbije (ZOS), who contributed her knowledge to this article.

Health risks

This lithium mine might sound appealing at first. It could provide the EU with a much-needed supply of this costly metal. But lithium is just that, a costly metal. Mining lithium is a costly process, not just financially, but also taxing on the environment and public health. To abstract lithium from soil, sulfuric acid is used. (Over)exposure to this acid can lead to skin irritation, vomiting and in the worst cases an increased chance of getting lung cancer. People that live close to lithium mines often report these symptoms and tend to have a shorter lifespan.

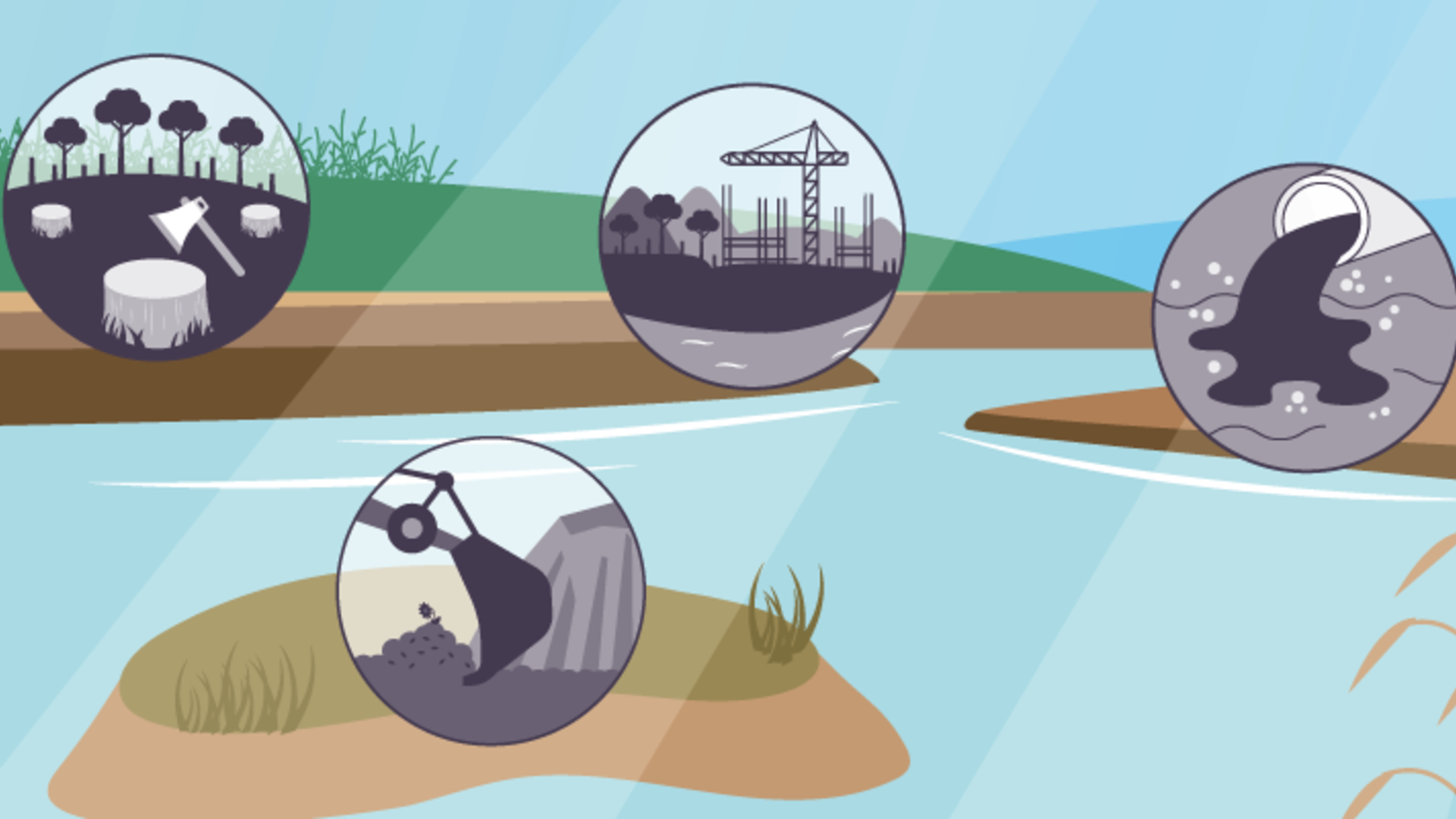

Contamination

Lithium has so far exclusively been mined in already water scarce regions, because of the risk of possible contamination of groundwater. The Jadar valley will be the first example of a lithium mine in a water rich, populated area. Something that can only be seen as an experiment as it has never been tried before. The Jadar river is a vital part of the valley, and it feeds into the Drina, one of the three major rivers in Serbia besides the Sava and Danube. Contamination in the Jadar river could thus be catastrophic for the entire water network in Serbia and potentially neighbouring countries. The Jadar valley has fast and complex underground water systems. A lithium mine that stretches far underneath the surface brings big risks for these water systems and the soil. The groundwater is what makes the valley one of the lushest valleys of Serbia, one that has withstood severe droughts at times when almost the entire country dried up. Because of this, it was able to provide most of Serbia with food, in a period where other harvests failed. But its future as a lifeline for the country will be at risk if the mining project continues.

Mining one ton of lithium requires 500,000 liters of water. This water will be contaminated with sulfuric acids as well as other chemical waste. With water becoming an increasingly scarce resource, even in Europe, this is not something Serbia can afford. This water is a life source for many of the inhabitants of the region. Generations of families have lived here, feeding themselves off this fertile land. Preliminary research in this area has already shown contaminated soil and deceased livestock, fueling growing concern among the local population.

Actors

The Serbian government led by authoritarian leader Aleksandar Vučić has struck a deal with the EU over investments in the country, especially with regards to the Jadar lithium mining project. An EU deal with an authoritarian and unloved regime in Serbia is not a popular decision among the Serbian people. The regime has been heavily criticized over decreasing democratic standards and increased oppression. Cooperation between the EU and Serbian government on an already controversial project has thus led to falling popularity of the EU among the population of Serbia.

The EU, however, was determined to secure a large amount of its need for the sought-after metal. The mine could provide lithium for 1.1 million electric cars. Just days after the Serbian government had reinstated Rio Tinto's mining license, a delegation of the vice-president of the Commission, the German government including the chancellor and a state secretary from the Green Party, and the CEOs of two large car manufacturers arrived in Serbia to sign a deal.

The German government has a special interest in this project because of its large car industry and its leading role in the European energy transition. The Greens being part of the governments mean that they have to defend its choice to invest in the lithium mining project, whereas its Serbian counterpart Zeleno-Levi Front has been part of the opposition against it.

The mining itself will be done by Rio Tinto, which is a big British-Australian mining company and the second biggest mining company in the world. It has a bad reputation when it comes to previous mining projects: for example, Rio Tinto was responsible for destroying an Australian Aboriginal sacred site while expanding a mine back in 2020 and in the United States the company has been held accountable for causing ecological damage including depleting and contaminating groundwater supply. The same is the case in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, often at the cost of local or indigenous populations. Add to this the fact that Rio Tinto has no experience mining lithium as it has primarily mined iron ore, copper and aluminum so far. All of this raises the concerns of the people living in the Jadar valley.

Reaction

Serbians have become increasingly disappointed and disengaged with politics after years of democratic backsliding, but this deal has sparked a fire against this particular government decision. Vučić has promised that investments will flow back into the country, but Serbians believe this will turn out to be yet another broken promise. They fear the money will flow into the pockets of government officials, shareholders and Rio Tinto. Corruption is daily business in Serbia, free and fair elections are long gone, and voter fraud is widespread. To the population, this mine embodies years of detrimental decisions under this regime. The Serbian people were quick to take to the streets after the project was announced. All layers of society participated in the protests, from farmers to left-wing activists. The Green Youth of Serbia (ZOS), IFG’s partner in Serbia, have been at the forefront fighting against this lithium mining project. Many protestors have already been locked up, followed and some have even been assaulted, demonstrating that the right to protest has come under great pressure.

Meanwhile the EU has continued backing the project. It does not seem likely that the Commission will pull out, even with the project under increased pressure. It appears the Commission hopes it can pull Serbia into its sphere of influence in order to increase democracy and fundamental rights, but seems to be achieving the contrary. Another possible downside of this increased cooperation could be that the access to lithium will be used as a geopolitical tool by the Serbian government.

Crossroads

What alternative approaches could the Commission take to this project? One option could be to urge the Serbian government to replace Rio Tinto with a different corporation. This will likely not be a popular decision among the Serbian population, who have already stated that they will only stop when the project is shut down completely. Another option is to ensure opponents get a seat at the table, so that their concerns can be taken into account. The EU could try and work towards a compromise together with opponents and the locals. If accession from Serbia into the EU ever becomes reality, it is in the best interests of the EU to have support from the general public. A pro-European point of view of the population together with EU accession could see Serbia move away from Russia as a close ally.

Paradigm shift

Wetenschappelijk Bureau GroenLinks has developed an Agenda for Action for groenlinks called ' Metals for a Green and Digital Europe ' and gave the following advice. Prioritise finding and developing alternatives for rare earth metals. There are other materials that can potentially replace lithium and have fewer negative effects on the environment, though these too can have negative effects or be less effective. A way to become more independent from countries like China, could be improving recycling efforts of rare earth metals. This will not make the EU self-sufficient as the projected amount of rare earth metals needed is not yet on the market, but it will give an impulse to a different approach towards these rare earth metals. Instead of focusing on giving everyone an electrical car, mobilization should be rethought across the EU. More affordable and accessible public transport being a focus point in this. Rare earth metals should be treated as such and thus be very careful with how and where to use them.

All in all, it can be concluded that this mining project is a divisive issue in Serbia. Consulting with the local population should be a priority for the EU in developing this mine, ensuring their voices are heard.

Sources:

Hajdari, U., Zimmermann, A., & Lau, S. (2024, 19 augustus). Serbia’s leader wins the West with promises of ‘white gold’ — but loses the people. POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/serbia-president-aleksandar-vucic-win-west-promise-white-gold-lose-people/

Higgins, A. (2024, 18 augustus). ‘Bad Blood’ Stalks a Lithium Mine in Serbia.The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/18/world/europe/serbia-lithium-mine.html

Mars Sa Drine. (2023, 3 september). https://marssadrine.org/en/general-information/

Momčilović, P. (2023, 13 juni). Serbia’s Lithium: Sacrifice Zones or Opportunity for Europe’s Peripheries? Green European Journal. https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/serbias-lithium-sacrifice-zones-or-opportunity-for-europes-peripheries/

Radar, N. B. (2024, 25 juli). Damage inevitable, maybe catastrophic: Oxford professor about the Jadar project. N1. https://n1info.rs/english/news/damage-inevitable-maybe-catastrophic-oxford-professor-about-the-jadar-project/

Wouters, R. (2021, oktober). Metalen voor een groen en digitaal Europa. Wetenschappelijk Bureau Groenlinks. https://www.wetenschappelijkbureaugroenlinks.nl/publicaties/metalen-voor-een-groen-en-digitaal-europa